"But the Holocaust"

“But the Holocaust” can no longer be a conversation ender when talking about Palestine and Zionism

“But the Holocaust” was initially conceived as one cohesive essay, but ended up being much too long for Substack’s platform, so I’ve broken it up into 3 parts, which will be released weekly.

I was raised with a very clear picture of what injustice looks like. The plight of my grandmothers, fleeing fascists halfway around the world. The millions who could not, or would not, abandon their homes and were displaced, slaughtered with ruthless efficiency. And the survivors returning to Poland, Romania, Hungary, Lithuania, who were harassed, heckled, brutalized and ultimately made into refugees on unfamiliar lands.

Stories of the Holocaust, now solidified in the history books, pass through generations and shape Jewish identities. From these stories, a sequential narrative has been crafted: that our liberation from concentration camps necessitated the establishment of a Jewish state. Today, the words “But the Holocaust” disarm legitimate critiques of Israel and its actions. Intentionally or not, this shutdown results in the erasure of another diaspora, the Palestinian diaspora.

Palestinians fled from a movement of land theft and ethnic cleansing in 1947-48. 800,000 who could not, or would not, abandon their homes and were displaced or slaughtered with ruthless efficiency. And the survivors of such atrocities were denied the right of return to Ayn al-Zaytun, Baysan, Haifa, Deir Yassin, Sa’sa and ultimately made into refugees on unfamiliar lands.

In the face of such historic and present injustice, we must ask ourselves: what does justice look like? Memories of the Holocaust offer a roadmap to many Jews.

Exploring how these roads are paved and what forces cement them is critical to unearthing paths that lead us astray. My own sense of justice is grounded in the experiences of my ancestors, particularly my grandmother-a Holocaust survivor and Holocaust studies scholar-who I admire greatly. Her story is integral to my identity as a Jew and is precisely why I feel so repulsed when the legacy of the Holocaust is twisted to justify war crimes and genocide against Palestinians. My Jewishness teaches me that justice looks like genuine human solidarity, the unconditional belief that our liberation is collective liberation, that we can not be free until every person is free.

Memories of the Holocaust take some people down a different path, a different sense of justice. Horror stories from the Holocaust culminate in deep seeded trauma, leading to a justice rooted in self-preservation and fear of others. For many, “But the Holocaust” is the end of the conversation when talking about Palestine and Zionism.

A single sentence written by Edward Said in Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims sparked my curiosity to ask the question why? Why does the legacy of the Holocaust rest differently in the minds of Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews?

“In order to break down the iron circle of inhumanity, we must see how it was forced, and there it is ideas and culture themselves that play a major role.” - Edward Said

I argue that Zionism -the political ideology that a Jewish state is essential for the survival of Jewish people -exploits people’s trauma to construct the concrete walls of exclusive statehood. To combat Zionism, we must reckon with the harsh reality that it exists both in the minds of a people and the policies of a state. That the state has immense political, military and economic power, is all the more reason to unravel the contradictions of its ideology and understand the psychological forces it exploits.

Beyond understanding, to build the movement we need to achieve a Free Palestine, we must be equipped to think critically about “the why.”

After all, it is the ability to ask the question “why” that offers us the most hope in a world that demands we blindly follow orders.

Why?

For those of you unsure about Zionism, it is my hope that thinking about the roots of why we believe and act the way we do might bring up some stirring questions for you. And for others working to dismantle Zionism, understanding the precise way it fixates in the brains of those under its spell just might be the magic needed to break its curse.

1947-48

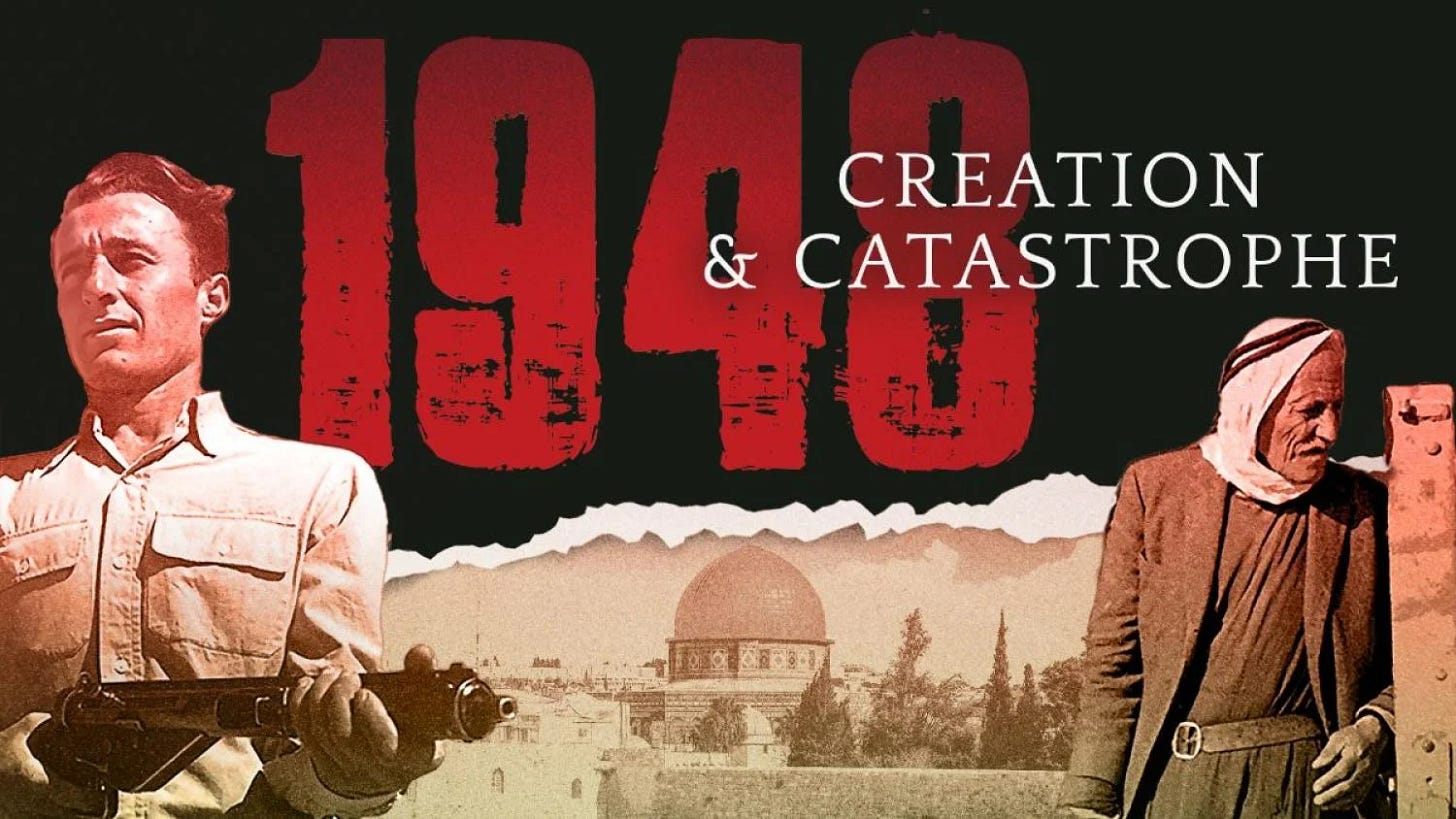

One of the most frequent remarks I hear from anti-Zionist Jews is: “How could Jews possibly have carried out the Nakba just years after experiencing a genocide?” In the documentary 1948: Creation & Catastrophe, Jewish veterans of the Nakba pull back the veil, openly discussing the atrocities they committed, some with remorse and some without, but all with a sense that their actions were in the best interest of their people. Under the guise that the only route of guaranteed safety was Jewish statehood, they stole Palestinian land, murdered civilians and displaced whole populations from their homeland.

This “Us Versus the World” mentality was not incidental. Zionist political leaders, who were plotting the creation of their state decades before the Holocaust, saw a great opportunity: the trauma of survivors and those hearing their horror stories could be easily manipulated. As the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end with UN partition, the Zionists were ready to act on their ethnic cleansing plan, dubbed “Plan Dalet.” Ethnic cleansing as defined by the Hutchinson Encyclopedia (and in theory adopted by the U.S. state department) is expulsion by force in order to homogenize the ethnically mixed population of a region. Because ethnic cleansing is universally acknowledged as a crime against humanity, the Zionists had to develop an accompanying narrative campaign to enlist soldiers and justify its crimes on the global stage. Weaponizing memories of the Holocaust would prove to be a crucial tactic.

Israeli historian Ilan Pappe in The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, provides a meticulous account of the ethnic cleansing operations during the 1947-48 Nakba. His narrative presents a consistent theme of Zionist manipulation. Without going into the weeds, the 1948 “Arab-Israeli War” was a sham (if you don’t believe me please read Pappe’s book). What was publicly depicted in the West and future Jewish state as a war for Jewish survival, was in reality won before it started. The only question was how much Palestinian land could the budding Jewish state ethnically cleanse leading up to and after its creation. The narrative of an impending “Second Holocaust” provided the political cover necessary to carry out the atrocities of implanting a Jewish state onto Palestinian land with impunity.

Pappe references first hand accounts of former Jewish soldiers describing the atmosphere ahead of ethnic cleansing operations. Before particularly cruel orders for Palestinian expulsion were given, “special political officers would come down and actively incite the troops by demonizing the Palestinians and invoking the Holocaust as the point of reference for the operations ahead, quite often the day after the indoctrinating event had taken place.” Behind closed doors, David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s ‘George Washington,’ and his political consultancy knew that despite their clear path to victory and statehood, this doomsday messaging would disarm legitimate critiques of the newfound state. When Palestinian and Arab militias retaliated for the slaughter of their relatives, Ben-Gurion would compare them to nazis and the casualties of their attacks as “victims of the second Holocaust.”

Despite this rhetoric, in the wake of the “Arab-Israeli War,” Zionist politicians were aware that unsavory comparisons could be reasonably drawn between the plight of Palestinians and Holocaust survivors. Israel’s decision to not involve the International Refugee Organization (IRO) in the Palestinian refugee crisis reveals this awareness. The IRO was the agency responsible to Jewish Holocaust survivors following World War II. Israeli leaders feared IRO involvement with Palestinians could lead to associations being made between Palestinian victims of the Nakba and Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

Blatant social engineering of a traumatized people by political elites begins to answer the question of “how could they?” The expression “hurt people hurt people” is insufficient. Rather, under the guise of preserving their own safety, deeply traumatized people were manipulated by a nascent state hungry for power into committing similar atrocities to those experienced by their relatives.

This brings up more questions for me that I don’t have clear answers to. What does it mean to hold the purveyors of an ethnic cleansing as secondary victims of their own dehumanizing ideology? What about in the context of a present genocide in Gaza, supported by the majority of Israelis? How do we reckon with and dismantle such deeply entrenched propaganda inseparable from a state’s existence where 41% of all Jews live?

Perhaps some answers lie in understanding the long lasting impact that weaponization of post-Holocaust trauma has on current Jewish perceptions of Zionism. To quote Pappe once again:

“For Israeli Jews to accept this [the events of the Nakba], they would have to recognize that they have become the mirror image of their own worst nightmare.”

Instead of this recognition and reconciliation (i.e. justice), misconstrued comparisons of Palestinians to nazis grew into a deliberate rhetorical strategy that persists to this day.

Stay tuned next week for part 2, Combatting Zionism Today. “But the Holocaust,” is a weekly exploration of why Jewish conceptions of Zionism are shaped by the Holocaust.

You can subscribe for free to be notified when I share new writing.

If you’re able to financially support my work, paid subscriptions allow me to spend fewer hours working at the deli and more hours writing! Free subscriptions and sharing with friends is also helpful and I am appreciative of each and every one of you.

Great post. Thank you.

Love the passion though not all of the ideas.