Losing Ritual

It started with the whole ‘not believing in God’ thing. In the first month of Hebrew School, the senior rabbi made a surprise visit to our religion class. She insisted we go around in a circle, sharing what God meant to us. Each of my peers, eager to impress, gave solid, uncontroversial answers: “God is the leader of the chosen people,” “God is the judge between good and evil, “God is all life and existence.” Then it was my turn. I was never skilled at censoring myself for authority figures, so when I earnestly shared: “God means nothing at all to me,” I first felt proud of my honesty, then embarrassed when my classmates failed to stifle harsh giggles, and finally dismissed by my rabbi’s scowl. While this was the first time I recall questioning my belonging in Jewish community, the story of losing ritual began generations ago, with a slow process of alienation.

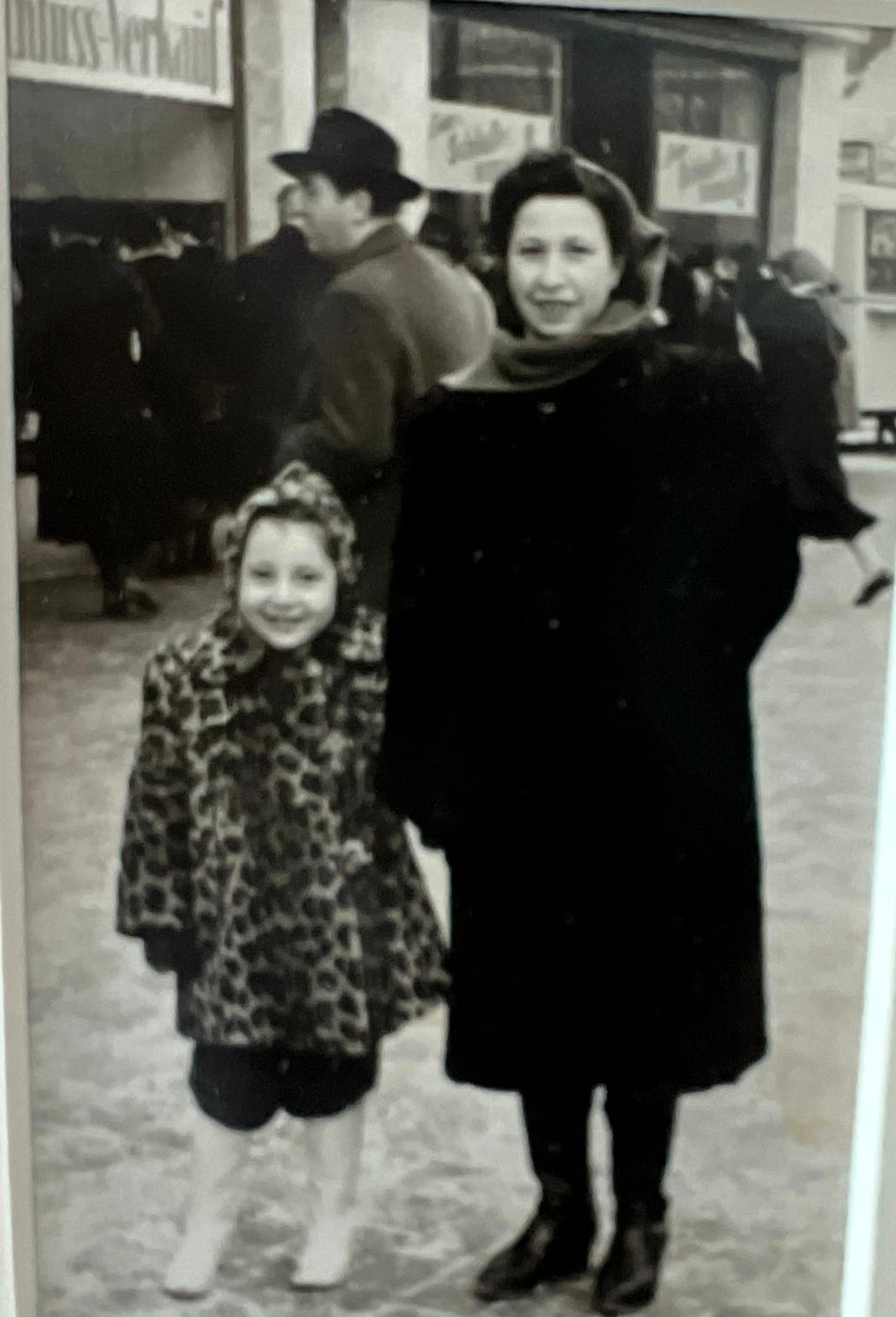

In Warsaw, before the Holocaust, my ancestors’ ritual practice was a mixed bag. My grandmother’s mother’s family was deeply religious. They observed the high holidays, went to synagogue every Shabbat, and kept kosher. My grandmother’s father's family was more focused on leftist politics than religion, although they maintained Yiddish ritual practices nonetheless. Both of my great-grandparents, Itzak and Lola, spoke Yiddish, read Hebrew and received a Jewish education. They were part of a tight-knit community in the Jewish sector of Warsaw, which included a wide range of religious, cultural, and political practices. When the Nazis invaded Poland, my great-grandparents and five other family members fled Warsaw for Brest1, then to Nyuvchim2, then Kyrgyzstan3, back to Poland after the War, displaced to Germany, then to Cincinnati4, then to the Bronx, before finally meeting up with relatives in Vineland, New Jersey.

Violent upheaval and near starvation tested their religious beliefs, their sense of God; however, they landed in a place with a large Jewish community where they could continue to be openly Jewish. In Vineland, there was a rift between “American” Jews and “refugee” Jews, the former of which held a haughty attitude towards the latter. Jewish refugees were not welcome in the town’s synagogue, instead celebrating high holidays in each other’s homes. The divide between Itzak and Lola’s ritual practice widened, as Itzak became a “three or four day a year Jew5,” while Lola lit the Shabbat candles every Friday and mostly kept kosher. My grandmother grew up in a household where Jewish ritual was present, but not emphasized. By the time she was an adult, and my mother was born, Jewish ritual had all but disappeared from her life.

My mother did not grow up learning Hebrew, attending synagogue, nor lighting Shabbat candles. She was not a part of Jewish community nor connected to Jewish ritual. When she was old enough to think for herself, she asked my grandparents if she could go to Hebrew school, and they refused. They feared she would encounter and eventually espouse stringent, conservative values in Hebrew School, which had been their experience with Jewish congregations in the past.

As an anti-apartheid activist in college, my mom’s alienation deepened when her progressive Jewish friends were vocal about South African apartheid but silent on Israeli apartheid. There seemed to be two beliefs among her Jewish peers–staunch support or apathy.

Despite her upbringing, my mom always yearned for a Jewish community. She suspected that it could offer a home for somebody who did not believe in God and was not a Zionist. When my siblings and I were old enough, she searched for a synagogue that would welcome an atheist, non-Zionist family. She eventually found a rabbi open to these beliefs, and so I started Hebrew school, but a few weeks in, that rabbi left and a new one stepped in. The new rabbi was not interested in hearing out the little boy resolute in his atheism.

Despite the early warning-signs, my parents insisted I continue my Hebrew School education. I never believed in God, but I was raised to believe that this does not preclude you from being Jewish. Jewishness contains multitudes, a range of histories, rituals, religious beliefs. None of these are mutually exclusive, and I felt a strong affinity for the history of my ancestors. I wanted to learn more about what they believed, what rituals they practiced, what struggles they endured. Hebrew School did not provide what I was looking for. Instead, the teachings of the Torah and our thousands year history all coalesced into a singular narrative: that Zionism was necessary to our collective survival, and the founding of Israel was the culmination of all our oppression and resilience.

Complexity be damned, this was the divine truth, ordained by an authority of God.

Eventually, my bar mitzvah came along. As I’ve shared in a prior story, during my torah portion interpretation, my rabbi cut me off mid sentence to angrily interject her Zionist reading of the text. She demanded that Moses’ teachings of sustainable land practices in Parashat Behar referred specifically to the modern state of Israel and proved our sacred duty to colonize that land. Never mind “wrestling with God”; clearly words that didn’t point towards the legitimacy of a nation-state were beyond consideration. My experience had confirmed my mother’s fear that to be Jewish meant to be a soldier for Israel and a follower of God. I was completely dejected, feeling that there was no place for me in Jewish community. My family gave up, leaving the congregation entirely. I would not return to synagogue for nine years.

I had lost ritual.

Until I found it.

Finding Ritual

As the years went by, I didn’t really consider what I had lost. In lieu of ritual practice, I developed an inclination for hyper-rationalism. Everything could be explained in tangible, scientific terms, most of which were yet to be discovered. My education reinforced this philosophy, particularly my high school economics class. My most engaging teacher taught macroeconomics, so I paid close attention and discovered I had a knack for conceptualizing economic theory. The theory offered tantalizing simplicity that I craved and I decided to continue my economics education in college. In the very first class, we learned the “Principles of Economics”: 1. Humans are rational. 2. Markets are good. 3. Economic growth is king. Feeling affirmed in my talents at calculating marginal utility, I grew increasingly disconnected from anything that wasn’t “rational.”

A pandemic, a water protector movement and two uprisings shook me out of this reductive philosophy, revealing the underbelly of the theory that had once captivated me. Disillusioned from capitalist economic theory, I searched for purpose elsewhere and eventually found organizing.

In my first organizing job, I worked closely with Indigenous Peoples whose organizing was grounded in land-based ritual practices. Organizing for Indigenous sovereignty, in solidarity with Indigenous Peoples–whose relationships with land is the foundation of resistance–was moving. It was also jarring, because I am not indigenous to any land, nor did I practice land-based rituals. Learning from Indigenous organizers stirred me to look within myself, delving into my own history and learning about the rituals of my ancestors.

I found the teachings of Rabbi Jessica Rosenberg, a Minneapolis-based rabbi. I learned about ‘radical diasporism’, the idea that those in the Jewish diaspora “get to know the land on which we live, honor the original inhabitants, and understand ourselves as interdependent parts of the ecosystems in which we dwell6.” I learned about the Jewish cycle of time, the unique offering to reflect that comes with each month. In the month of Sivan, we celebrate Shavuot and honor harvest practices that have sustained us for millennia. During Av, we commemorate Tisha B’av by grieving the loss of Jewish–and all other–sacred sites destroyed by empire. And every year, Tishrei offers a new beginning, a new year to grow and deepen ritual practice.

With each new lesson about Jewish diasporism, I was simultaneously inspired by the depth of Jewish rituals, and astonished by how far away from them I had grown.

I started putting some of these teachings into practice. I connected with a group called “The World to Come,” a Jewish diasporist group who organize and share opportunities to practice Jewish ritual in the Twin Cities. Steadily increasing my commitment to ritual, I attended Rosh Hashanah services, a beeswax candle-making workshop, a Jewish diaspora crafts market and monthly Shabbat.

The strides I made to reconnect with Jewish ritual were filled with intense moments. On November, 23rd, 2023, I stepped foot in a synagogue for the first time in more than nine years. On a whim, I decided to attend a morning service at a local synagogue. Not knowing what to expect, I was initially apprehensive when I walked into a room with a dozen other people sitting in a tight circle. I had not entered a Jewish religious sanctuary in a long time and I feared my discomfort would be palpable. My nerves quickly gave way to gratitude as I was received warmly. I closed my eyes and let the songs sung by others hold me, the serene sounds of prayer melting my frosty disposition and I slowly let my guard down, until I was singing too. At one point, we paused to introduce ourselves and I immediately broke down into tears as I attempted to describe how and why this was my first time in a synagogue in almost a decade. The tears did not stop, yet somehow I felt no embarrassment at breaking down in front of complete strangers. I only felt the intensity of beginning to heal. Of finding ritual.

This return to ritual was so emotional because I realized the deep sense of loss I had experienced. The conflation between Zionism and Judaism in institutional Jewish spaces had taken away my ability to connect with Jewish ritual without compromising my values. Although this conflation seems antithetical to the core Jewish concept of “wrestling with ideas,” the pervasiveness of Zionism often leaves no room for wrestling. It diminishes a religion, a history, a set of ritual practices with a breadth of meaning and interpretation, into a singular, deceitful narrative of Jewish-supremacist nationalism. By entering a synagogue for the first time since I was a child, I had taken a leap of faith that despite this all, maybe there was a place for me in Jewish community. And when I found like-minded people who embraced me, it all began to unravel: all the weight of the loss I had experienced, all that Zionism and generations-long alienation had stripped from me, all the injustice. And all I could do was cry and cry and cry.

I soon realized that like (but different from), the Indigenous organizers I had worked with, ritual and organizing could be intertwined. For one, it is precisely within Jewish tradition to fight against injustice and stand in solidarity with those oppressed by empire. I was no longer an anti-Zionist organizer in spite of being a Jew, I was an anti-Zionist organizer because I am a Jew. One instance of ritual-protest was last Chanukah, when chapters of Jewish Voice for Peace across the country held disruptive actions in protest of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Myself and hundreds of Jews commemorated Chanukah, a holiday celebrating the miracle of persistence in the face of oppression, by blocking a bridge and singing “ceasefire now, let Gaza live.” Through ritual-actions, I learned that the teachings of Jewish ritual can be a force of solidarity rather than colonization.

Today

I don’t think I will ever believe in God. I do, however, believe in the interconnectedness of life and feel a deep connection to my ancestors. For some people what I am describing is God. For me, these connections are less mystical than they are ecological, physiological, maybe even spiritual. My ancestors are in my DNA, my bloodstream, my synapses, my emotions, shaping the way I formulate thoughts and relate to the world. The more I learn about them, the more drawn I am to Jewish ritual.

A couple weeks ago, “The World to Come” invited me to share a d’var torah–a talk that sets the tone of a Shabbat service–about my recent trip to Warsaw. Not long ago, the idea of leading part of a Shabbat service in front of more than twenty people would have been inconceivable. But the transformation I had undergone, and relationships I had built, compelled me to accept. Sharing words about my ancestors and the lessons we can learn from their history was a wonderful experience and a great honor. It was only possible because of the teachings of diasporist Judaism and the belief that I do belong in Jewish community. I am so grateful for everybody who has supported me in this ongoing process of searching for ancestral connection in Jewish ritual. Learning about and practicing rituals held by millennia of my ancestors brings me wholeness beyond belief.

You can subscribe for free to be notified when I share new writing.

If you’re able to financially support my work, paid subscriptions allow me to spend more hours writing! Free subscriptions and sharing with friends is also helpful and I am appreciative of each and every one of you.

Border town in Eastern Poland, controlled by Soviets during WWII

Formerly of soviet union, present day Russia

Where my grandmother was born

They were placed in Cincinnati by a Jewish refugee assistance agency

This history of my ancestors’ relationship with Jewish ritual comes from conversations with my grandmother, who interviewed her relatives and documented their experiences.

For Times Such as These, A Radical’s Guide to the Jewish Year by Rabbi Ariana Katz and Rabbi Jessica Rosenberg

This is powerful. Thank you for sharing.

I feel so blessed to be with you on this journey, Joseph! Thank you for sharing so generously and powerfully.